Here’s my sermon/reflection from Greenfield Church’s services this weekend. If you’d like to watch the whole service, you can find it here: https://youtu.be/q1nZ0ei3RzM. It’s based on the readings Luke 23: 32-43 and Jeremiah 23:1-6, which are here: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke+23%3A32-43%3B+jeremiah+23%3A1-6&version=NIV

Could you recognise a king?

Of course, we’d all probably recognise our new king, even if it still feels a bit weird to call him King Charles instead of Prince Charles, and even though we haven’t got used to singing “God save the King” instead of “God save the Queen”.

And even if you weren’t sure what he looked like, you’d know if he was coming: the streets would be lined with people, security would be be ultra-tight, and when he arrived you’d see the motorcade and the Royal car itself, complete with flags on the bonnet etc.

You’d recognise the King.

But what if you didn’t find yourself in the midst of a prepared royal visit? What if you were somewhere where you wouldn’t expect to see a king (or queen)? Would you recognise a king there?

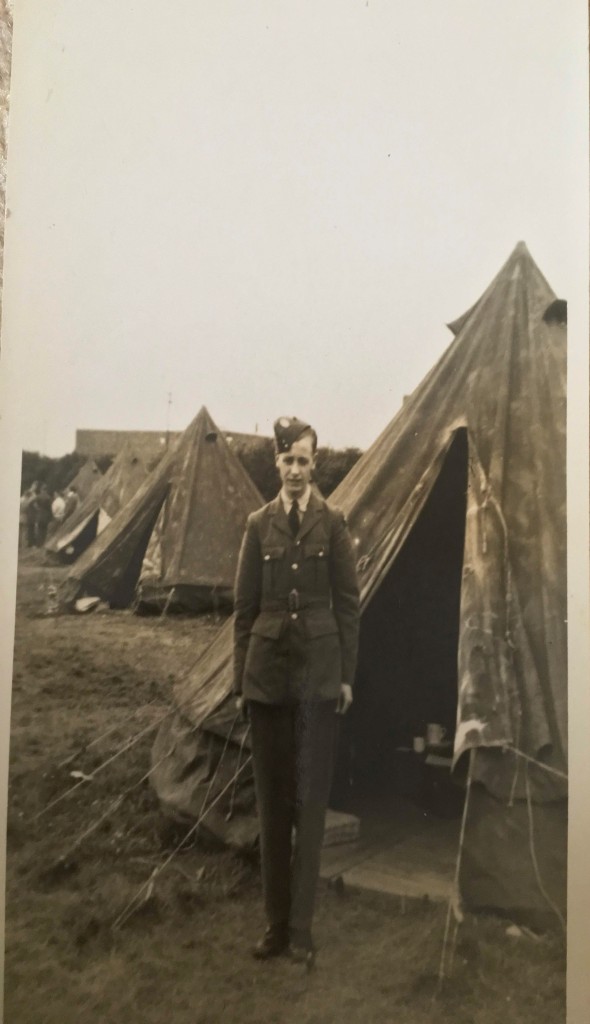

During the Blitz in London in WW2, as people emerged to discover their homes and businesses had been bombed to smithereens, the King and Queen of the time famously visited the East End to see the damage and the survivors. And looking at the pictures now, it seems strange to see the king in his military uniform and the queen in her fine dresses and furs standing amongst the rubble and ruins.

But if you’d been there, you’d have recognised them, even if it was the last place you expected to see them.

But would you recognise a king who’s being executed?

And I don’t mean, would you know who they were.

Kings have been executed throughout history, and part of the point is to see the hated ruler being given his comeuppance.

No: would you recognise as your king someone who’s being put to death?

The unrecognised king

Many of those gathered round the cross of Jesus couldn’t – wouldn’t – recognise Him as king.

In fact, seeing Him on the cross was the sign they’d been looking for that He wasn’t the true king.

The leaders of the people, the soldiers, even one of those executed with Him: it was inconceivable to them that this man, this weak, dying, humiliated man could ever have been a king.

Sure, the sign above his head called him “The King of the Jews”. But it was a parody, a farce, a mockery of the man whom many had claimed would be their king – as well as a warning to others not to try to claim the same thing.

And so the leaders mocked him: “Let him save himself if he’s the messiah of God!”

And the soldiers joined in: “If you are the King of the Jews, save yourself!”

And one of the criminals joined them, too, though perhaps with a hint of desperation in his voice: “Aren’t you the Messiah? Save yourself and us!”

Oh, they knew a king alright – and they knew that this wretch couldn’t possibly be one.

“Remember me…”

But there was one person saw Jesus differently.

One person who was capable of recognising Him as a king.

That other criminal who put the first one in his place and who spoke of Jesus’ innocence.

“Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom”.

Wow! What an incredible thing to say!

That either of them had a future beyond their certain death…

That that future could involve a kingdom…

That Jesus could be the king of that kingdom.

How could he say any of that? How could he call the dying Jesus a king? How could he claim a place in his kingdom?

Well, perhaps this criminal knew that there on the cross, Jesus was doing what He’d always done: Putting himself amongst and welcoming the sinners, the law-breakers, the despised and rejected.

The ones whom everyone else said were write-offs, Jesus said were actually lost and needed finding – and that He had come to do just that.

What it takes to recognise a king

And now, even on the cross, even as His life is unjustly taken from Him, He does it again. He takes His place amongst the criminals and becomes King to one of them; the one who is ready to recognise what true kingship means:

Not pageantry and high security.

Not wealth and finery and gold and jewels.

Not military might and political power.

No, the true King is the one who’ll go and find the lost, who will go looking for all those whom the leaders and rulers have abandoned and bring them back and offer them paradise.

That’s what the Jeremiah passage is talking about: the people had been abandoned by those who were supposed to lead them to safety. Now they were scattered in exile – but God would send a new shepherd, a new king, who would go after them, find them, and make sure they could never be scattered again.

That’s why this criminal recognised Jesus as King: because He was the One who was doing exactly that, He was the One who would build a kingdom out of the lost, the hopeless and the helpless, a kingdom that would outlast even the empire that was putting Him to death.

Could you?

The criminal recognised Jesus as this King, even as they both succumbed to death.

Will you?

Could you accept as your king someone who willingly took his place amongst the criminals, those who deserved the death sentence?

Could you accept as your king someone who was willing to undergo the pain of the cross and the humiliation of the taunts and teasing of the powerful who saw him there?

Could you accept as your king the One who gave Himself over to death, who deliberately made Himself look like a failure?

And will you see Him as the One, true king of the kingdom that is like no other, yet which will outlast them all?

It’s harder than you think!

It means seeing yourself as unworthy, just as that criminal did.

It means recognising your need of Him and His death on the cross for you.

It means humbling yourself to accept the reign of someone who looked a fraud and a failure in the eyes of so many.

And if you will recognise Him as your king, what will you do about it?

Because the way that King Jesus chose – the way of the cross and all it brings – is the way He calls us to follow, too.

Will you walk this way, even if it means sacrifice?

Will you choose, not the path of ease or glory, but the path of serving others and putting them even before yourself, without seeking reward or repayment?

Will you show others what it means for Jesus to be your king, and call them to do the same, even if they ignore or misunderstand you?

But if you can…

Because if you will, then something glorious awaits you: paradise.

Not just “a room in heaven” as we often picture it. Paradise here was just the waiting room, the stop-off point before the final destination:

Resurrection.

Life.

Eternity with Jesus, the One who came looking for us, died so that we could be found, and who offers us something more wonderful and lasting than anything the kingdoms of our world could give.

Can you recognise the king? Will you accept Him as your king?

Cover picture by Jametlene Reskp, unsplash.com